Primordial events in Theology and Science support a life/death ethic

by Martin J. Rice

Martin Rice (Ph.D.) has written and taught in science and theology, including teaching at Christian Heritage College School of Ministries in Brisbane where he completed his Graduate Diploma in Ministry Studies. This article is a shortened and adapted version of a paper, given at the Contemporary Issues in Ministry Conference, 2003, at Christian Heritage College, Brisbane, Australia.

Martin Rice (Ph.D.) has written and taught in science and theology, including teaching at Christian Heritage College School of Ministries in Brisbane where he completed his Graduate Diploma in Ministry Studies. This article is a shortened and adapted version of a paper, given at the Contemporary Issues in Ministry Conference, 2003, at Christian Heritage College, Brisbane, Australia.

Share good news – Share this page freely

Copy and share this link on your media, eg Facebook, Instagram, Emails:

Primordial events in theology and science support a life/death ethic, by Martin Rice:

https://renewaljournal.com/?p=3362&preview=true

An article in Renewal Journal 20: Life:

Summary: Primordial events in both theology and science support a basic life/death ethic

Several remarkable coincidences between some primordial events described in the Bible and, independently uncovered through the programmes of modern science, facilitate the derivation of basic, binary ethical principles. Such broadly-based principles are potentially widely influential, by virtue of their primordial and grand, contextualizing character. Whilst the time-scales of these events are always likely to be contentious, the biblical and scientific events themselves are strikingly similar, and generally not contentious. Although it could be argued that the coincidences are artificial, the Bible having influenced the scientists’ interpretation of their data, an even stronger argument can be made for independence of the two data-sets. Such coincidences, therefore, suggest nature itself (for example the night sky, the reef, and the rainforest) advertises a grand context; a life/death context, that conditions all ethics. Common principles, derived from the science and the theology of primordial events, clearly modulate the viewpoint that ethics are an entirely culturally-determined, social construct. They also add an ethically instructive note to our enjoyment of the harmony of our spectacular environment.

This hybrid paper, is offered with something of the attitudes of Arthur Peacocke (1996, p.94), who writes, “But to pray and to worship and to act we need supportable and believable models and images of the One to whom prayer, worship and action are to be directed.”; and of Hugh Ross (1999, p.47), who says, “Rather than elevating human beings and demoting God, scientific discoveries do just the opposite. Reality allows less room than ever for glorifying humans and more and than ever for glorifying God.”

Introduction: evangelism goes out and meets people where they reside (Acts 1:8).

Scientifically trained people sometimes ask challenging questions of the Christian faith. For example, among believers it is not usual to ask, “Why did God create a universe having the observable characteristics of our one? Or, “What is the connection between the invisible God and our visible space/time reality?” Or, “How does eternal Life compare with earthly life?” If asked, they are usually answered with general truths, like, “It is to give God glory”, or, “Because God is a loving, creator God”, or, “Because God’s Word says so and I believe it”. However, most contemporary thinkers seek more technically specific answers. Failing that, they are likely to turn off from hearing the Gospel. In addition, ethical relativism thrives in situations where a connection between God and human society is perceived as distant, tenuous, or imaginary. Such negative outcomes make it pertinent for theologians, students of the Bible, ethicists, and evangelists to be aware of the actual questions being asked, and to work at addressing specific issues, in terms of appositely contextualized biblical revelation (see Carson, 2000). Jesus guaranties the power of the Holy Spirit for those who will witness to the Gospel in diverse situations (Acts 1:8); however, it is not reasonable to expect God’s Spirit to over-ride sound logic and reason, since these come from the same Spirit (e.g. 1 Kings 4:29; Romans 12:2; Ephesians 1:17; 4:23; Hebrews 8:10; 1 Peter 1:12,13). As Mark Ramsey, a well-known preacher, puts it, “The Bible says you are transformed by the renewing of your mind, not by the removal of your mind!”. This means transformed cerebration but also standing out, being different, being a loving community of ‘resident aliens’ in an over-individualised world (see Carson, 1996, p.478).

The substantial contributions of intellectuals who submitted to God, such as Isaiah, Saul of Tarsus, Luke the physician, Augustine of Hippo, Hildegard of Bingen, etc., demonstrates that evangelizing thinkers could be worth while. Great minds are created by God to do great good but, without Christ, they may do great harm. Evangelising intellectuals is a priority: what the University thinks today, Society will enact tomorrow! Might our society be reaping a bitter harvest from its earlier neglect of sowing well- reasoned seed, and its failure to cultivate the fields of academia with the Gospel? Empowered by the Holy Spirit of God, academics who are Blood-washed, born-again, and Bible-believing, should be able to produce wiser and more powerful intellectual advances. Did Jesus ever say to steer clear of academe and the intellectual knowledge enterprise? Matthew 13:52 would suggest otherwise; here the learned of God’s Kingdom are told to become wise in applying both ancient and contemporary knowledge. Matthew 6:33 emphasises, that for those who are submitted to God’s rule, everything else follows. Pearcey and Thaxton (1994), and Murphy (2003), provide excellent philosophical underpinning for the harmonizing of science and theology.

Thoroughly intellectual Christians are capable of the best. J. Rodman Williams (1996) has set a bench-mark in producing, Renewal Theology – Systematic Theology from a Charismatic Perspective. C. Peter Wagner is another author from the pentecostal stream, who writes at a high academic level. In addition, there are many from the evangelical stream (most famously C. S. Lewis) able to reach the intellectuals, including thinkers like Francis Schaeffer, Ravi Zacharias, Os Guiness, Nancy Pearcey, D. A. Carson, Gordon D. Fee, and many others. In Australia, Kirsten Birkett, author of Unnatural Enemies – an introduction to science and Christianity (1997), edits Kategoria, an excellent, Christian, critical review, published by Matthias Media, Kingsford, NSW. A new frontline, research journal has appeared called Theology and Science (Volume 1, Number 1, April 2003, sponsored by The Centre for Theology and the Natural Sciences, Berkeley). Whilst some of the papers in this journal and its progenitor (CTNS Bulletin) may be insufficiently founded on Holy Scripture for many believers, they do at least address controversial issues in the theology, science, philosophy, and society interface, and thus invade the academic strongholds of atheism, with ideas of God. With the confidence of God’s judgment against worldly wisdom (1 Corinthians 3:18-20), the academy of pentecostal thinkers is surely even more mandated to invade every domain of thought with the light, life, logic, and love of Jesus Christ (e.g. Colossians 2:2-4).

To the ends of the Earth: a scientific world-view

Much that is written in science and technology has powerful theological overtones (usually without the conscious knowledge of its authors!) and often has implications for human culture and ethics. In 1959, C.P Snow’s The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution appealed for greater acknowledgement of the relationship between the arts, government, and science. Snow would have been amazed how drastically things had changed, 40 years on, when Willimon (1999) wrote, “It has been one of the great postmodernist discoveries that almost everything is opinion. Almost everything is value laden. We have no way of talking about things except through words, and words, be they the words of science or the words of art, are more conflicted than they may first appear, more narrative dependent, story based. Science is as ‘religious’ as religion.” Historian, Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1970), alerted scientists to the tremendous influence their imagination has in directing the path of science.

Philosophers of science (such as A.F. Chalmers, in the 1999 edition of his, What is this

thing called Science) are now thoroughly cognizant with the apparent impossibility of finding a truly objective foundation for the scientific endeavour. That is not to say that science isn’t largely objective; after all, no one has to think twice before getting into a motor vehicle or using a computer. It does mean, however, that any opinions that science expresses on why its products work, or what the larger context is, are fraught with contradictions. Science on its own is able to tell us how things work (within limits), but it is unable to say why they work, nor what the overall grand story is. The “why” question is intimately linked to questions about the origin and destiny of all things, and it is here that science becomes inarticulate. In fact, as this paper moves to demonstrate, science needs Christian revelation to support its major world-view, and to complete its contextual integrity. Science and Christianity are great partners but awful opponents. The common view that they are separate and irreconcilable ways of knowing [or NOMA, non-overlapping magisteria {cf. the late Stephen J. Gould’s Rocks of Ages (1999)}], should never be acceptable to a Christian. In contrast, Richard H. Bube (1995) has derived a taxonomy of the variety of possible productive relationships between the Christian faith and science. Carlson (2000), provides a thorough debate of this issue. In this paper there is no attempt to dictate from parts of Holy Scripture as to what scientists must believe.

Creation Scientists have fully occupied that area, loyally and creatively defending the Word of God, and producing a library of literature and multi-media (e.g. see web sites: http://www.icr.org; http://www.ChristianAnswers.Net; http://www.answersingenesis.org; etc.). Whereas, much of Creation Science can be seen as a form of apologetic defense and of confrontational rhetoric {e.g. In Six Days – Why Fifty Scientists Choose to Believe in Creation, edited by John F. Ashton (2001)}, the approach outlined in this paper is frankly evangelical, and essays to be eirenically logical. This, different type of approach, does not overtly contradict but reaches out to encounter science where it is, and enlivens and elevates it through biblical insights, built around a philosophy that could be called ‘Invasion Theology’. At no stage does invasion theology attempt to prove science wrong by quoting scripture, but neither does it compromise God’s Word by syncretising it with un-Christian views of the meaning of scientific discoveries. The vision is to meet an enquirer on their own scientific territory and, right there, to demonstrate that God’s Word stretches into science, and that the living Word is able to lead scientists intellectually and personally into the arms of Christ. The apostle Paul was comfortable to be a Jew with Jews, a Gentile with Gentiles, and weak with the weak. Paul teaches Christians to focus on winning as many souls for Christ as possible, by any fair means that work (1 Corinthians 9:20-22). He also warns Titus to avoid futile arguments (Titus 3:9). In the same ethos, invasion theology consciously evades religiosity. For a variety other points of approaches to the Genesis issue, see Hagopian (2001).

The most profound place of encounter between science and Christianity is at the primordial events that generated the observable universe we live in. To find out ‘how science thinks’ is not problematic; a web subscription to the weekly, world-leading science journal, Nature, is sufficient to provide clear information on the latest discoveries and developing theories. Science is renowned for the instability of its theories of origins, but most of the time in recent years it has considered our universe of space/time to have originated from nothing, by means of a ‘Big Bang’. In big bang theory, a non-space/time ‘singularity’ becomes (against all statistical probability) unstable, and generates the commencement of our universe, in the form of a gigantic bubble of expanding space, light, heat energy, and time. The energy then produces matter: subatomic entities such as quarks, that eventually cooperate to form the simplest of all chemical species, hydrogen atoms. Billions of tons of hydrogen become attracted together by gravity and eventually form stars. Stars are hydrogen-consuming, thermonuclear, fusion reactors, generating heat and light on a grand scale. Stars also manufacture the lower atomic weight elements, and, when a star eventually ages and explodes as a supernova, it also synthesises the higher atomic weight elements. This generates most of the chemical elements of the Periodic Table and widely scatters them through space, to form inter-stellar dust clouds, which are able to aggregate by gravitational attraction, to form planets, satellites, meteorites, and comets. Some of these may then revolve around a star, to form arrangements, such as we observe in our own planetary system. Science then proposes that (if conditions are right on the surface of a planet) microbial, plant, animal, and even human life may develop. Generations of human societies accumulate knowledge and skills to the point where they invent science and technology, develop radio-telescopes and cyclotrons, and begin speculating about primordial events! This story depends upon profound cooperation (including loss of personal identity) among the diverse varieties of cosmic entities. It is the standpoint of this paper that far too much emphasis has been placed on competitive interactions and this now needs to be adjusted to reveal the extent to which our universe depends upon cooperation.

Just as science has originated a detailed narrative to explain the birth of our universe, it also attempts to extrapolate from its data to predict how the universe may die. The earth first, scorched by an expanding red-giant sun; the universe next, as it attains maximum entropy and time ceases. Such a simplistic, atheistic cosmology is deeply unsatisfying to any thinking, feeling human being. In the cosmogenesis of unaided science (which in parts can yet be extraordinarily detailed and well substantiated) everything happens by accident, with no meaning beyond the mechanics of existence and survival; ethics are simply a by-product of an arbitary requirement for social stability. Science’s non-theological universe is thus deadly cold; a place of frustrated hopes; a frantic, meaningless interlude of light, life and pain-wracked consciousness, caught between two periods of unstructured, lifeless, utter darkness. This raw scientific vision mocks at the beauty and meaning of light and life and love, by chaining it between preceding and succeeding eons of darkness, death, and empty loveless-ness. Truly, “a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.” (Shakespeare’s Macbeth, Act 5, Scene 5). The very rawness of this unadorned scientific worldview cries out for the Christian ministry of wisdom, faith, encouragement and, indeed, for deliverance.

The indispensable Word of God: the Bible adds meaning to science’s worldview

The Biblical story of primordial events is largely found in the early chapters of the book of Genesis. The first part of the first chapter of John’s Gospel is crucial, and there are key verses in the Psalms, Job, Isaiah, Matthew, Romans, 1 Timothy, Hebrews, 1 and 2 Peter, Jude, and Revelation. The Christian understanding of the origins of our universe can never be separated from Christology, since it pleased God the Father to make his Christ the creator of all that exists, in the spiritual, as well as the material universe; the Christ antedates all things, and entities only obtain their meaning and function from him (Colossians 1:15-19). Polkinghorne (1988, p.69) writes, “One’s instinct to seek a unified view of reality is theologically underwritten by belief in the Creator who is the single ground of all that is.” The challenge for a Christian thinker is to come to such a knowledge of God’s Word, as to be able to provide a bridge from Christ to the lost world of scientism, described at the end of the section above. In order to achieve that, it may be necessary to re-examine cherished beliefs (like the sexual transmission of ‘original sin’) that have come down the centuries from early church fathers, like Augustine. A thoroughly biblical worldview is required, to meet science and the intellectuals at the place where they labour today, not where they loitered many centuries ago (cf. Mt 13:52). Paul instructs Timothy to make full use of the holy scriptures (verses that are full of God’s life-giving breath) to teach, train, and equip for good works; and to correct error, and rebuke wrongdoing (2 Timothy 3:16). Inspired by the Lord, the Holy Spirit, this surely must be a life-giving journey into God’s reality, and never a matter of dead religion.

In such a short paper as this, it is not possible to fully develop major theological points, and that work has to be left for another venue. However, to develop the basic argument, summary positions have had to be taken regarding the nature of God, the origin of evil, the sequence of primordial events, the reason for our universe to exist, and the predicted outcome of it all. Much further reading is available, and authors such as Southgate (1999) have developed excellent teaching programmes at the interfaces of science and theology. Multi-disciplinary courses in this area are proliferating and becoming popular in many good universities.

It is not hard to convince many scientifically educated modern or post-modern thinkers that science is inadequate to measure ethical qualities such as: faithfulness, kindness, justice, mercy, humility, righteousness, love, joy, peace, holiness, forgiveness, patience, self control, etc. This then permits the suggestion that there are entities beyond the containment of our space/time universe; a suggestion confirmed by fundamental physics in regard to the mathematical value of constants governing the forces that subtend the material universe. Our universe very clearly has inputs from outside its ‘box’. That those inputs are highly tuned to produce circumstances conducive to human existence is also demonstrable. The scientific evidence for design (and hence the Designer) grows stronger every year (e.g. Dembski and Kushiner, 2001). A scientifically-literate enquirer might then be led to consider the possibility that the God of Christians is truly the same person as the unseen designer of our universe, the originator of uniquely human persons; an inspiring, self-giving God of light, reason, life and love.

Regarding the nature of God, the Bible clearly states that he alone is immortal, dwells in unapproachable light, and is impossible for a human being to see (1 Timothy 6:16); that God is love (1 John 4:8), and is spirit (John 4:24); that his invisible qualities can be clearly learned from unbiased examination of the world around us (Romans 1:20); and that everything we need to know about God has been revealed to us by the life and teachings of Jesus Christ of Nazareth (e.g. Philippians 2:6; John 6:36; 10:30; 14:9).

Since God, and God’s dwelling place, are full of light, life, love, holiness, and perfect order (e.g. 1 John 1:5), the question arises as to where the disorder described in Genesis 1:2 comes from. What is the origin of the pre-existent darkness, formless emptiness, and watery depths (perhaps a hebraism for ‘rebellion’). This question is rarely addressed theologically but, in the context of outreaching to those scientists aware of the yawning nullity proposed to precede the Big Bang, it is especially pertinent. Theologically, the answer can hardly be less than that the Genesis 1:2 situation, described by Moses, is evidence for the revolt of Satan and his rebel angels. Jesus said that he saw Satan fall like a bolt of lightening and that could well refer to an incident before the creation of our universe (Luke 10:18). Darkness in scripture is almost always (though not invariably) associated with evil (2 Corinthians 6:14; Ephesians 5:11; 2 Peter 2:17; Jude 6,13, etc.). A foundational proposal, here called ‘Invasion Theology’, is that a pre-existing negation of God’s immortal, life-giving love, a rebellion, locked in the deepest darkness, has been laid bare, and exposed in its minutest detail, by the Christ of God. It is proposed that Christ achieved this by invading that dark, chaotic pre-primordial place with our universe of light, life and love. This concept is bolstered by 1 John 3:8, when the verse is taken as a statement regarding the eternal work of the Christ, not just his earthly mission revealed in Jesus of Nazareth. In that sense, when Jesus says, “It is finished” (John 19:30), are there not overtones of his unceasing work, that started with the most primordial of events (Gn 2:2)? Whilst this may be an unusual view to theologians, it functions well as a bridge between the understanding of primordial events proposed by science and that revealed in the Bible. Invasion theology makes it almost inevitable that there would be a deceitful, death-dealing serpent loose in God’s Garden, at the ‘start’ (Genesis 3:1-4)! Invasion theology would view Adam, Eve and their children as delegates of God, mandated to extend the invasion throughout the earth, revealing and destroying the various levels of the princedom of darkness. As God’s people, Israel inherited the same sacred task, and Christ’s church is commissioned for similar work today.

Finally, Jesus Christ appeared in the flesh and, by his life and teaching, comprehensively demonstrated the victory of life over death. The invasion was complete, empowered and now to be extended to every creature. The resurrection of Christ is, in that sense, the most important event of cosmic history. The Resurrection guaranties his words regarding the forgiveness of sin, his prophesies about end-time events and the regeneration of all things. These are processes and events beyond the direct reach of science, though the evidence for Christ’s resurrection is objectively excellent (Stroebel, 1998).

Consequences of an invasion theology worldview: a basic binary ethical overview

A crucial point in any scheme of ethics is the definition of GOOD (e.g. Honderich, 1995, p.587). From the invasion theological perspective, ‘good’ is seen in the invasion of negation. That is, God’s activity in creating light, logic, life, and love; bringing into being a whole cosmos of meaning, reason, beauty, and worship. This may provide a way out of the dilemma first formulated in Plato’s Euthyphro, in that good is good both because God commands it and because of what it enacts (Honderich, op. cit.). It may be thought that there could be no coincidences here between theology and science, simply on the grounds that whilst ‘good’ is a proper object of study for ethics and theology, it falls outside the boundaries of science. Surely science is concerned only with the accuracy of data and the productivity (truth) of its hypotheses, theories, and laws? However, upon reflection that judgment might have to be revised. Science simply cannot avoid conceding that those factors that enable it to exist and to operate successfully are essentially ‘good’. Science did not exist, nor could it exist, in the pre-existing darkness of negation. Such a darkness and negation are not neutral, they are inimical to, and clearly subvert, the essential foundations of science itself, and so science would not be remiss in referring to them as objectively ‘evil’.

Factors such as light, logic, life, and love are essential for the very existence of science. Without light scientists could not see, without logic (part of wisdom) there would be no rational basis for science, without life there would be no humans to work in science, without love and cooperation our society would be so violent as to afford insufficient opportunity for science. Science must admit that the pre-primordial darkness of negation (revealed in the Bible and independently described by science) is evil and its invasion by light, logic, life, and love is good. The work of establishing order, understanding, and cooperation in our universe is unarguably the basis for the scientific endeavour; any resurgence of chaos and confusion is an anti-scientific force. So at its very heart, science is far from being an ethically-neutral discipline. This truth may come as a shock to most practicing scientists and technologists! Factors that facilitate science are unconsciously accepted as ‘good’, and those that degrade the scientific process are ‘bad’. Working scientists are in the habit of applauding research work as either ‘good science’ or denigrating it as ‘bad science’. To be meaningful and productive, science relies completely upon the immanence of logic and reliability in the universe, upon the integrity and skill of the scientists themselves, on the probity and standards of the community of scientists, and ultimately upon the sustaining interest and/or support of Society.

Peacock (1990, p.129) quotes atheist, Stephen Hawking, “Why does the Universe go to all the bother of existing? Is the Unified Theory so compelling that it brings about its own existence? Or does it need a Creator, and if so, does he have any other effect on the universe?” Peacock (1990 p.132) writes that Hawking, examining the uniformity of the initial state of the Universe, concluded that, so carefully were things chosen that, “it would be very difficult to explain why the Universe should have begun this way, except as the act of a God who intended to create beings like us.” Peacock (1990, p.143) also writes, ‘in a letter of January 1633 . . . Galileo wrote, “Thus the world is the work and the scriptures the word of the same God.” Truth itself is one, yet lies make it into a binary system. Peacock (1990, p.88) again, describes Fred Hoyle’s attempt to dispense with the idea of a creation moment by introducing a steady-state model, based on ‘continuous creation’ at the centre of the Universe and dissipation at the edges; an effort that was criticized by Stanley Jaki as, “the most daring trick ever given a scientific veneer”! Science is full of such binary ethical judgments; and examples range from honest mistakes, through weak thinking, right up to outright fraud and corruption of the scientific process. Scientific truth is subject to the same limitations and degrading influences as any other branch of truth and, indeed, the created universe itself. It, we, and God’s own Spirit all groan over this painful situation (Romans 8:22,23,26). The whole cosmic enterprise is attacked and harassed, being subjected to frustration and decay, living in hope of the emergence of humans who are pleasing to God (Romans 8:21,22). The whole of creation finds fulfillment in the revelation of the true followers of Christ; who are the harvest the universe is scheduled to produce (Romans 8:19). The book of Revelation is primarily concerned with the final exposure and destruction of the rebellious work of the devil, and the identification of the faithful co-workers of Christ. In one sense, the whole cosmic story is summarized in those two events, both of them giving great glory to God.

Independently, Christianity and science have revealed remarkably coincident views of primordial reality:

- Good is the desirable overall context and precedes evil;

- Evil is an aberrant subset that separates from good;

- Good is logical, orderly, consistent and reliable;

- Evil is unreliable, treacherous and chaotic;

- Good, by its nature, invades evil;

- Evil resists and corrupts good;

- Good does not rest until evil is eliminated.

The visible reveals the invisible: binary ethics gazes out at us, wherever we look

Of all the visually spectacular features of our universe, the greatest must surely be the night sky, viewed from a high place or country area, free from obscuring clouds, air pollution, and light contamination. The awesome beauty and breathtaking wonder of the endlessly diverse, and seemingly countless, stars, and of our Milky Way galaxy, beggar rational description. In our age of science, an observer can be expected to read much more meaning into that scene than simply its awesome beauty. Primordial negation is the backdrop, a thing of timeless darkness: energy-less, substance-less, lifeless, inhuman, loveless; a murderous place of death, darkness, deception, and hate. But countless beautiful lights burn in that darkness; time extends its merciful reign; planets revolve around suns; life flourishes on planetary surfaces, and it challenges the very teeth of negation; consciousness bursts forth, accompanied by conscience; literature and the arts flourish, and the dear Lord becomes known by name. Is it any wonder that God drove his prophets and his people into the wilderness so often, where the visible sky teaches of the invisible majesty of the Lord? The scientific details of modern cosmology contains many more parables that supports the ideas of invasion theology and of a basic binary ethic.

Australia still has some relic rainforests remaining. They are places of extraordinary biological variety, productivity, and unusual longevity; highly diverse and highly stable ecosystems. Rainforests rarely have any one species in large numbers, instead they seem to be knitted together by levels of multiple mutualism. Cooperation between species is their dominant motif. Rainforests advertise to humanity the advantages of unity and mutual help, as effective means of withstanding the assaults of chaos and destruction.

The Great Barrier Reef is justly one of Australia’s most renowned biological resources and arguably the largest living thing on planet Earth. The GBR is about 2,000 km long, occupying an area of about 200,000 square km, where the requirements for clear, unpolluted, shallow, warm, salty, moving water are satisfied. The GBR depends for its existence upon a minute organism – the coral polyp. Without countless trillions of these tiny anthozoans, building their colonies and providing food and shelter to a dazzling array of much larger and more sophisticated animals, there would be no reef. The coral polyps themselves are of about 400 varieties. Their beautiful colours are mostly provided by the symbiotic algae that live within their bodies. The glory of the reef is thus sustained, at its base, by the humble mutual service of two very different types of simple organism. The life of corals, though simple, provides for a profusion of amazing, and often subtly complex living beings (including delicious species of fish, crustaceans and mollusks!), that would otherwise not exist. The many ethical messages of this scenario need little emphasis.

It is remarkable that though the night sky, rainforests, and the reef are some of the most photographed objects in existence, yet their use as teaching examples for ethics courses would not be so well known. They contain countless spectacular examples of invasion theology and its perennial ethic of the boldness of light, transparency, order, cooperation, and life penetrating and flourishing over the spiteful negation of concealment, darkness, chaos, antipathy, and death.

Conclusion:

It is hoped that this paper’s melding of science, theology, ethics and nature provides a useful starting point for thinking about the very foundations of life and death. Certainly the postmodern dilemmas (e.g. “The pursuit of knowledge without knowing who we are or why we exist, combined with a war on our imaginations by the entertainment industry, leaves us at the mercy of power with no morality.” Zacharias, 2000, p.23) cries out for an objective reality. Perhaps science and theology, in an uncharacteristic symbiosis, are together becoming strong enough to point convincingly to the Rock of reality.

Bibliography

Ashton, J. F., editor (1999). In six days. Sydney: New Holland.

Birkett, K. (1997). Unnatural enemies. Sydney: Matthias.

Bube, R. A. (1995). Putting it all together. New York: University Press of America.

Chalmers, A. F. (1999). What is this thing called science? Brisbane: UQ Press.

Carlson, R. F. (2000). Science and Christianity. Downers Grove, Ill.: IVP.

Carson, D. A. (1996). The gagging of God. Leicester: Apollos.

Carson, D. A. (2000). Telling the truth. Grand Rapids, Mich.; Zondervan.

Dembski, W. A. and Kushiner, J. M., editors (2001). Signs of intelligence. Grand Rapids,

Mich.: Brazos.

Gould, S. J. (1999). Rocks of ages. New York: Ballantine.

Hagopian, D. G., editor (2001). The Genesis debate. Mission Viejo, Cal.: CruxPress.

Honderich, T. (1995). The Oxford companion to philosophy. Oxford: OUP.

Murphy, N. (2003). On the role of philosophy in theology-science dialogue. Theology and Science 1:79-93.

Peacock, R. E. (1990). A brief history of eternity. Wheaton, Ill.: Crossway.

Peacocke, A. T. (1996). God and science. London: SCM.

Pearcey, N. R. and Thaxton, C. B. (1994). The soul of science. Wheaton, Ill.: Crossway.

Polkinghorne, J. Science and creation. London: SPK.

Ross, H. (1999). Beyond the cosmos. Colorado Springs, Col.: NavPress.

Southgate, C., editor (1999). God, humanity and the cosmos. Edinburgh: T & T Clark.

Stroebel, L. (1998). The case for Christ. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan.

Williams, J. R. (1996). Renewal theology. Grand Rapids, Mich.; Zondervan.

Willimon, W. H. (1994). The intrusive word. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans.

Zacharias, R. (2000). In Carson, D. A., editor (2000).

© Renewal Journal #20: Life (2007, 2012) renewaljournal.com

Reproduction is allowed with the copyright included in the text.

Renewal Journals – contents of all issues

Book Depository – free postage worldwide

Book Depository – Bound Volumes (5 in each) – free postage

Amazon – Renewal Journal 20: Life

Amazon – all journals and books – Look inside

All Renewal Journal Topics

1 Revival, 2 Church Growth, 3 Community, 4 Healing, 5 Signs & Wonders,

6 Worship, 7 Blessing, 8 Awakening, 9 Mission, 10 Evangelism,

11 Discipleship, 12 Harvest, 13 Ministry, 14 Anointing, 15 Wineskins,

16 Vision, 17 Unity, 18 Servant Leadership, 19 Church, 20 Life

Also: 24/7 Worship & Prayer

Contents: Renewal Journal 20: Life

Life, death and choice, by Ann Crawford

The God who dies: Exploring themes of life and death, by Irene Alexander

Primordial events in theology and science support a life/death ethic, by Martin Rice

Community Transformation, by Geoff Waugh

Book Reviews:

Body Ministry and Looking to Jesus: Journey into Renewal and Revival, by Geoff Waugh

Renewal Journal 20: Life – PDF

Revival Blogs Links:

See also Revivals Index

See also Revival Blogs

See also Blogs Index 1: Revivals

Click here to be notified of new Blogs

FREE SUBSCRIPTION: for new Blogs & free offers

Share good news – Share this page freely

Copy and share this link on your media, eg Facebook, Instagram, Emails:

Primordial events in theology and science support a life/death ethic, by Martin Rice:

https://renewaljournal.com/?p=3362&preview=true

An article in Renewal Journal 20: Life:

Renewal Journal 19: Church – PDF

Also in Renewal Journals Vol 4: Issues 16-20

Renewal Journal Vol 4 (16-20) – PDF

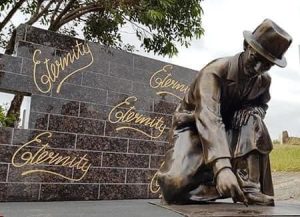

Sydney Harbour Bridge, 1 January 2000

Sydney Harbour Bridge, 1 January 2000