The Mystics and Contemporary Psychology

by Irene Alexander

Irene Alexander, Ph.D. (UQ) wrote as the Dean of the School of Social Sciences at Christian Heritage College, Brisbane, which offers a Bachelor of Social Science degree that includes majors in Counselling and Biblical Studies, as well as post graduate awards in Counselling and Human Studies. This article was presented as a paper given at the Contemporary Issues in Ministry Conference, October 31, 2002, at Christian Heritage College, Brisbane, Australia.

Irene Alexander, Ph.D. (UQ) wrote as the Dean of the School of Social Sciences at Christian Heritage College, Brisbane, which offers a Bachelor of Social Science degree that includes majors in Counselling and Biblical Studies, as well as post graduate awards in Counselling and Human Studies. This article was presented as a paper given at the Contemporary Issues in Ministry Conference, October 31, 2002, at Christian Heritage College, Brisbane, Australia.

Renewal Journal 19: Church – PDF

Share good news – Share this page freely

Copy and share this link on your media, eg Facebook, Instagram, Emails:

The Mystics and Contemporary Psychology, by Irene Alexander:

https://renewaljournal.com/2012/05/20/the-mystics-and-contemporary-psychology-by-irene-alexander/

An article in Renewal Journal 19: Church:

Many Christians, across denominations and backgrounds, have been rediscovering the heritage of their Christian faith, particularly the mystics of earlier centuries. The mystics are men and women who have somehow found God in a way that allows them to experience God’s reality in the depths of their being and have often passed on profound truths that can enable us to come closer in our walk with God.

Many of the truths these men and women have experienced have also begun to appear in other forms in contemporary society. Tacey (2000) suggests that in earlier times the traditional church structures were valid ‘containers for spirituality’, but that for many the institutionalised church structures no longer seem relevant and they are seeking other ways to find and express their spirituality. Counselling and therapy have become, as it were, another container for spirituality – a way for people to find meaning in their lives, to connect with their pain and see how it leads them to deeper truth, and deeper connection with God and others.

Exploring containers for spirituality relevant for this century it is helpful to be aware of past themes of relating to the Divine. In seeking to journey with others – both Christians and not – it is useful for us to have some understanding of timeless truths that have been lived by those of past centuries as well as ideas that contemporary researchers are discovering – or, in fact rediscovering. This article introduces a few of the themes of the mystics and shows their parallel in contemporary thought.

The Journey

Indeed ‘the journey’ is one of those themes. All beginning students of psychology and counselling dip into ‘human development’ or ‘development across the lifespan’ and learn about the theories of Piaget, Kohlberg, Erikson and Fowler which give us ways of interpreting the life stages in relationship to cognitive, moral, psychosocial and spiritual development. The recognition that life is ‘a journey’ through different stages, different ways of perceiving reality, different ways of relating to God and others, is an important part of twentieth century psychology. Although the concept of ‘age and stage’ has been strongly critiqued there is a general recognition that there are recognisable patterns across the lifespan, awareness of which can facilitate individual understanding and development.

Fowler’s (1981) stages of spiritual development, for example, have helped many people recognise that the changes in their faith are less to do with ‘backsliding’ than with healthy growth and maturing. Thus the often black-and-white faith of teenage years is replaced with a more individual, analytical faith in the twenties and thirties, and then a more inclusive re-visiting of ideas and experience in mid-life. It is recognised then, that each individual is likely to change in the way he or she views God, relates to a community of faith, and expresses spirituality.

This concept of an ongoing journey and individual differences and experiences along the way is one that numbers of the mystics have explored.

Teresa of Avila, a sixteenth century Spanish Carmelite, used the metaphor of the rooms of a castle to illustrate the spiritual journey. The first three stages of the journey involve a move from sporadic interest in relationship with God and time spent with God to a more steady relationship, but a tendency to focus on outward practice rather than inner self. The fourth stage is the turning point to a true inner journey and resting in God, with acceptance of grace and Spirit over law. The final three stages are characterised by union with God in an increasingly steady and mutual relationship. There still remain the dark periods and pain of surrender but also an intense desire and ecstasy of union with God. The Appendix gives more detail from The Interior Castle (Welch 1982).

Coe (2000) uses a contemporary of Teresa, John of the Cross, in his writing (see below) to trace similar developmental stages from biblical, psychological and spiritual perspectives. He notes the differences between pre-conversion, beginner and later stages using the ideas of our love of God ‘for Pleasure’s sake’, ‘for Love’s sake’, ‘for God’s sake’. He shows the importance of the ‘dark nights’ in the transformation and maturing process.

Interestingly, as Thompson (1984) points out, modern psychology has been helpful in reconnecting with the mystics. “When Teresa of Avila described the soul as an interior castle which most people never explore, she was stating truth we needed Freud and Jung to demonstrate. In our fragmented society, in which we are alienated from our inner resources, we remain largely dismissive of the most ancient and neglected spring of wisdom in Western Culture, its mystical tradition” (p. 42).

Freud and Jung then, twentieth century psychoanalysts, recognised, as Teresa of Avila did four hundred years earlier, that many of us defend against the inner work of bringing into our consciousness our desires, pain, blockages, fears. For Teresa this work was essential to bring us into deeper relationship with God and each other. A knowledge of the patterns of the journey – whether seen from Teresa’s movement through the Interior Castle, or through Fowler’s stages or Maslow’s hierarchy of needs to the self-giving of true self-actualisation – can help the traveller find the way to further growth and wholeness.

Spiritual formation

Another aspect of the journey which has become a popular focus recently is the recognition that we need to be intentional about the process of the journey – an emphasis on ‘spiritual formation’, the ‘inner life’. Modernist education left our generation with a legacy of intellectual and doctrinal propositions as a measure of our spirituality. That is our faith and orthodoxy were assessed by whether we believed the right doctrines, whether we could answer catechismal questions correctly. In contrast pentecostal and charismatic churches emphasised the experience of God through the spirit. Believers’ spiritual development may be seen by how they respond actively in worship, or believe in miracles, or exercise spiritual gifts, and the evidence of the fruit of the Spirit in their lives.

This shift from an emphasis on the cognitive, intellectual, rational to the more experiential and emotional has been a general shift in society’s way of understanding reality. Indeed contemporary psychology and counselling are also shifting from a more cognitive emphasis to a focus on the whole person, acknowledging the importance of the emotions, experience and relationship. However, we are still learning how to balance the cognitive and the emotional, how to use experiences and relationships to develop the ‘inner life’ toward psychological and spiritual maturity.

Says Willard (2000), “We have counted on preaching, teaching, and knowledge or information to form faith in the hearer, and have counted on faith to form the inner life and outward behaviour of the Christian. … The result is that we have multitudes of professing Christians who well may be ready to die, but obviously are not ready to live, and can hardly get along with themselves, much less others.”

There is a close comparison then, between contemporary psychology’s emphasis on inner work, and the growing awareness that we need to be intentional about our spiritual growth. Intentional spiritual formation is thus an understanding of the process of how spiritual growth occurs, indeed how Christ is formed in us (Galatians 4:19). May (1982) explains spiritual formation as “all attempts, means, instructions, and disciplines intended towards deepening of faith and furtherance of spiritual growth. It includes spiritual endeavours as well as the more intimate and in-depth process of spiritual direction” (p. 6).

Spiritual disciplines

Another parallel then between contemporary ideas – both psychological and theological – and the teachings of the mystics is the recognition that the faith journey – or the journey to maturity – is a long slow process, not just a quick-fix, or an impartation of knowledge. Spiritual formation is a process which involves a shaping of the inner life, and therefore a living of the outer life which reflects relationship with God, shown in responsiveness to God and to others. The spiritual disciplines have long been acknowledged as a part of spiritual formation, an important part of the growth process.

The spiritual disciplines have been recognised in more and more recent books for example Disciplines of the Holy Spirit by psychologist and pastor Siang-Yang Tan, and The Active Life by educator Parker-Palmer. The spiritual disciplines include, solitude and silence, as well as prayer and meditation. The Protestant work ethic has often distanced us from these, or turned what is supposed to be a refreshing encounter with the Divine, into another kind of work and striving. The mystics call us to rest in God, to pray by sitting silent in his presence (as in The Cloud of Unknowing by an unknown fourteenth century English mystic), to allow his word to refresh our souls.

Contemporary psychology also emphasises these processes. Many popular non-Christian books have similar emphases Care of the Soul by Thomas Moore (1992), is one of the earlier books, but a browse in any bookshop now turns up numbers of books encouraging harried Westerners to slow down, meditate, get in touch with the Divine. This is not meant to imply that these books are the same as Christian faith and practice, but simply draws the parallel in recognising the development of the whole person – mind, soul and spirit, and the need for processes which enable people to care for their soul, to develop their relationship with the transcendent, to mature in their emotional and relational responses.

The true self

Another part of the journey recognised in some schools of psychology, especially the Jungian, is the leaving of the false self and the discovery of the true self. Pennington (2000) describes the development of the false self through the usual childhood developmental processes of gaining love and approval for achievement and performance. “[Children’s] value depends on what they have, what they do, what others – especially significant providers, real or potential – think of them. … This is the construct of the false self” (p. 31). The false self is formed by fulfilling all the internalised rules and requirements to gain acceptance and approval by those we value – including God. We often are not even aware that we have transposed these beliefs on to God and yet we spend our lives living according to certain internalised patterns of behaviour that we think will gain God’s approval.

In contrast, the true self is found in abandonment to God. It is most easily identified by remembering an experience in which we had a revelation of God’s utter acceptance of us – a time when we knew as deeply as we have known anything that we are loved simply for who we are – there is nothing we can do – it is, after all, all grace. In that moment of deep knowing we are most in touch with the true self.

Pennington helps us identify this by comparing it to how we feel when we know ourselves loved, in love. “One of the great experiences of life is that first experience of being in love and being loved. Of course our parents love us. They have to, or so it seems, and siblings, too. But the first time someone loves us for no other reason than that person has in some way perceived our true beauty, our true lovableness, we float. We are ecstatic. For we have seen in the eyes of the lover something of our own true beauty. The only way we really see ourselves is when we see ourselves reflected back to us from the eyes of one who truly loves us” (2000, p. 46).

The true self is who we most truly are, having shed all the striving for acceptance, approval and control. Again Pennington elucidates: “When we perceive more and more clearly our true self in God, we are all but dazzled by the wonder of this image of God. But at the same time we are profoundly humbled. For we know that we are made in the image and likeness of God. … And we know that, but for the grace of God, it could be wholly lost” (2000, p. 49).

Ruffing (2000), in a careful examination of relationship with God and the developmental process points our how our self-image and God-image correspond – that is, as we are able to accept the reality of God as a God who loves unconditionally we are more and more able to see our selves as lovable. It is a revelation of the astoundingly accepting love of God which first reflects to us the image of the true self, and it is the grace of God which keeps us in the place of ceasing striving and letting our hearts, as Rilke (1996), says “simply open”.

Ruffing (2000), in a careful examination of relationship with God and the developmental process points our how our self-image and God-image correspond – that is, as we are able to accept the reality of God as a God who loves unconditionally we are more and more able to see our selves as lovable. It is a revelation of the astoundingly accepting love of God which first reflects to us the image of the true self, and it is the grace of God which keeps us in the place of ceasing striving and letting our hearts, as Rilke (1996), says “simply open”.

In his poem Rilke, a German poet, writing at the turn of the twentieth century, shows how often our portrayals of God keep us in the false self and thus hide our selves from our selves and from God. He suggests that an overemphasis on God as King may keep us in the position of being subservient and therefore not truly our selves.

We must not portray you in king’s robes

You drifting mist that brought forth the morning.

Once again from the old paintboxes

we take the same gold for sceptre and crown

that has disguised you through the ages.

Piously we produce images of you

till they stand around you like a thousand walls.

And when our hearts would simply open

Our fervent hands hide you.

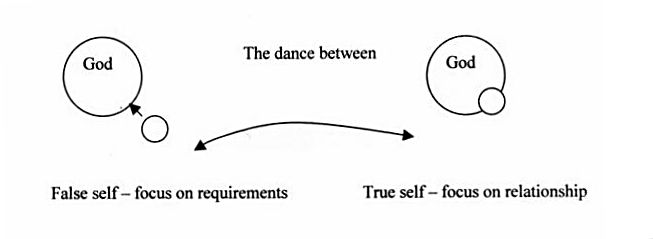

Psychological and spiritual growth then, have both been recognised to be a letting go of false images of self (and of God), and discovering the true self, as well as finding the God who is. This letting go of the false self fits with Jesus saying we must die to self (Matt 16: 24-25) – we have to let go of all the ego strivings which we cling to in order to look good in the eyes of the world. Instead we are to find the true self, as Jesus went on to say – what does it profit anyone if they should gain the world but lose the true self – the ‘soul’ (Matt 16: 26). The reality is that we tend to dance back and forth between the true self and the false self, hopefully learning more and more to lose the false self and find the true (Rohr 1999).

Muto (1991) notes that it is impossible to lose a self we do not have. She believes that until we know something of who we are, strengths and weaknesses, we cannot die to the false. “People can become quite sick if they try to annihilate what does not exist” (p. 17). This is a stark reminder that the process of life is a journey – which cannot be hurried by jumping ahead of where we really are. Muto suggests that some success and a ‘good dose of self-esteem’ are needed for the next, often dark, stages of the journey described by John of the Cross, a sixteenth century mystic, who introduces us to an essential part of the journey generally avoided by the West – the journey of darkness and of suffering.

Dark night of the soul

In many ways the modern world, especially medicine, has taught is to believe that freedom from suffering is possible. Modern psychology can easily be seen to be allied with the medical model, and therefore the flight from suffering, for example with the quick prescription of antidepressants. However psychological research shows that the longer process of therapy – especially changing of negative thought – is an important part of dealing with depression and anxiety. Other psychological models emphasise the need for ‘emotional work’, the painful process of staying with anger, rejection, fear, grief and anxiety, in order to trace their development and to change destructive relational patterns which continue to produce these unresolved feelings. There is then a growing awareness that engaging with pain and suffering is a way to wholeness, to a more authentic personhood.

The mystics were certainly more attuned to this truth than the West has been for many decades. John of the Cross in particular has introduced us to the ‘dark night of the soul’. This expression has been used in various ways but basically refers to the episodes of not experiencing God, of finding ourselves bereft of our usual sense of God’s presence and therefore having to seek God in a different way, to trust God’s presence and reality and love in spite of a lack of experiencing these in ways we are used to. It can be compared with ‘wilderness’ times, where everything we used to draw sustenance from seems to have deserted us and we find no comfort – and yet in the long run it leads us to deeper relationship with God.

John of the Cross draws much from the content and language of Song of Solomon, and the dark night of the soul can be found in the times where the maiden goes looking for her beloved and cannot find him (Song of Sol 3:2, 5:6) and yet in this story too, she comes up from the wilderness ‘leaning on her Beloved’ (Song of Sol 8:5). John notes that during the dark night there is a time of dryness when both the things of God and the things of the world lose their appeal. Further, “All support systems are found wanting, and only a naked faith sustains the pilgrim” (Welch 1982 p. 145).

John of the Cross’s poem, ‘The Dark Night’, (translated by Kavanaugh 1979), indeed shows us the dark night, but reveals even more vividly the wonder of the Love we can find in this experience:

One dark night

Fired with love’s urgent longings

– Ah, the sheer grace! –

I went out unseen

My house being now all stilled;

In darkness, and secure,

By the secret ladder, disguised,

– Ah, the sheer grace! –

In darkness and concealment,

My house being now all stilled;

On that glad night,

In secret, for no one saw me,

Nor did I look at anything,

With no other light or guide

Than the one that burned in my heart;

This guided me

More surely than the light of noon

To where he waited for me

– Him I knew so well –

In a place where no one else appeared.

Oh guiding night!

O night more lovely than the dawn!

O night that has united

The Lover with His beloved,

Transforming the beloved in her Lover.

Upon my flowering breast

Which I kept wholly for Him alone,

There He lay sleeping,

And I caressing Him

There in the breeze from the fanning cedars.

When the breeze blew from the turret

Parting his hair,

He wounded my neck

With His gentle hand,

Suspending all my senses.

I abandoned and forgot myself,

Laying my face on my Beloved;

All things ceased; I went out from myself,

Leaving my cares

Forgotten among the lilies.

John of the Cross leaves us in no doubt that the experience of separation from God, the periods of suffering and unrequited longing, are, in the end nothing compared with the union with God which results.

The lesson which the mystics teach us over and over is that knowing God, and finding a love relationship with God is the highest meaning of life. “Let not the wise man glory in his wisdom; neither let the mighty man glory in his might. …let him … glory in this, that he understands and knows me, that I am the Lord” (Jeremiah 9: 23-24).

Knowing: intuitive and relational

So we find that these wise men and women recognised that knowing God was not about intellect and knowledge but rather another kind of knowing all together. As the unknown author of The Cloud of Unknowing explains: “It is God, and he alone, who can fully satisfy the hunger and longing of our spirit which transformed by his redeeming grace is enabled to embrace him by love. He whom neither men nor angels can grasp by knowledge can be embraced by love. For the intellect of both men and angels is too small to comprehend God as he is in himself” (Johnston 1973, p. 50).

And further Julian of Norwich, after fifteen years of pondering the meaning of the revelations given to her by God said “‘You would know our Lord’s meaning in this thing? Know it well. Love was his meaning. Who showed it you? Love. What did he show you? Love. Why did he show it? For love. Hold on to this and you will know and understand love more and more. But you will not know or learn anything else – ever!’ So it was that I learned that love was our Lord’s meaning. … In this love all his works have been done, and in this love he has made everything serve us; and in this love our life is everlasting. Our beginning was when we were made, but the love in which he made us never had beginning” (Wolters 1966, p. 212).

Jones (1985) explains the two contrasting traditions of knowing with the use of images, pictures, symbols and the way of emptying, the via negativa, “sometimes called apophatic (which means against or away from the light) or contemplative. …. This way of not-knowing lies at the heart of the way of believing that helps me live as a believer” (p. 25). And de Mello (1990) explains how deeply this is part of the Christian faith quoting Aquinas of the thirteenth century: “This is St Thomas Aquinas’ introduction to his whole Summa Theologica: “Since we cannot know what God is, but only what God is not, we cannot consider how God is but only how He is not.”…This man was considered the prince of theologians. He was a mystic, and is a canonized saint today” (p. 127).

While contemporary psychology continues to emphasise scientific method rather then ‘not-knowing’ there has certainly been a shift from an emphasis on objective, rational knowing to include relational and intuitive knowing can allow the West to embrace relationship with the Divine as part of their intellectual as well as spiritual lives. This shift from the cool, objective ways of knowing to the warmer, relational, subjective ways of knowing allows something of the delight in God to be experienced. This is seen in the writings of a Persian mystic, Hafiz, of the fourteenth century:

What is the difference

Between your experience of Existence

And that of a saint?

The saint knows

That the spiritual path

Is a sublime chess game with God.

And the Beloved

Has just made such a Fantastic Move

That the saint is continually

Tripping over Joy

And bursting out in Laughter

And saying “I surrender!”

Whereas, my dear,

I am afraid you still think

You have a thousand serious moves.

Contemporary western society then, is rediscovering important themes of the earlier Christian traditions. The writings of the mystics – of the journey, the intention of development of the true self, the process of inner work through pain, darkness, disciplines of silence and ‘soul-care’, and the acknowledgement of ways of knowing that are intuitive and relational – can inform our present journey and ways of spiritual and psychological development.

Appendix: The Interior Castle of Teresa of Avila (Welch 1992)

Stages of the journey:

1. Self knowledge: Conscious effort at prayer and reflection, but often so involved in worldly things that it is still caught by these impediments. Glimpses of true self-knowledge (both beauty and sin) in the light of God’s love and mercy.

2. External practices. There is a steadier commitment to prayer, but the call of God is more externally mediated – through books, sermons, other people and events. Teresa notes “you cannot begin to recollect yourself by force but only by gentleness”.

3. Both inner and outer journey – i.e. a commitment to prayer, and also to acts of service and Christian behaviour. A tendency towards a ‘religious ego’, a sureness of knowing the whole story which leads to a certain self-righteousness. A certain restlessness, and desire for more leads the traveller on. Teresa uses images of serpents as being those things which distract the pilgrim from God.

4. This stage is a major transition in life, the beginning of the inner journey. Grace and Spirit become dominant rather than self-striving. Initially prayer is still the active prayer of meditation but rapidly becomes an absorption in God, the ‘prayer of quiet’. “Like a good shepherd with a whistle so gentle … this shepherd’s whistle has such power that they abandon the exterior things in which they were estranged from Him and enter the castle” (p. 104). The image of this stage is fountains built over the source.

5. The prayer of union – a deepening of contemplative prayer. However experiences of union tend to be brief. The symbol Teresa uses is that of a white butterfly which is being transformed in the cocoon and emerges in the next stage.

6. An intensification of the union which involves both intense pain and times of ecstasy, both a dark night of the spirit and an experience of betrothal, a wounding and a drawing out of the arrow.

7. The union with God is completed. This is the very centre of the castle where the King dwells and it is characterised as marriage. There is a deep interior peace – as well as an emphasis on service in the world.

References:

Barrows, A. and J. Macy, J. (Trans). (1996). Rilke’s book of hours: Love poems to God. New York: Riverhead.

Brown, I. (2001). “The kingdom within: The inner life of the person in ministry.” Renewal Journal, 18, pp. 5-11.

Coe, J. H. (2000). “Musings on the dark night of the soul: Insights from St John of the Cross on a developmental spirituality.” Journal of Psychology and Theology, 28, 4, 293-307.

de Mello, A. (1990). Awareness. London: Fount.

Fowler, J. W. (1981). Stages of faith: The psychology of human development and the quest for meaning. New York: Harper Collins.

Johnston, W. (ed). (1973). The cloud of unknowing and The book of privy counselling. New York: Image.

Jones, A. W. (1985). Soul making: The desert way of spirituality. New York: Harper Collins.

Kavanaugh, K. (Trans). (1979). The collected works of St John of the Cross. Washington: Institute of Carmelite Studies.

Ladinsky, D. (1996). I heard God laughing: Renderings of Hafiz. Walnut Creek, CA: Sufism Reoriented.

May, G. G. (1982). Care of mind, care of spirit. New York: Harper.

Moore, T. (1992). Care of the soul. London: Piatkus.

Muto, S. (1991). John of the Cross for today: The ascent. Notre Dame, IL: Ave Maria. (Original work published 1584)

Palmer, P. J. (1999). The active life: A spirituality of work, creativity, and caring. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Pennington, M. B. (2000). True self false self: Unmasking the spirit within. New York: Crossroads.

Rohr, R. (1999). Everything belongs: The gift of contemplative prayer. New York: Crossroads.

Ruffing, J. K. (2000). Spiritual direction: Beyond the beginnings. New York: Paulist.

Tacey, D. (2000). Re-enchantment: The new Australian spirituality. Sydney: Harper Collins.

Tan, S-Y. and Gregg, D.H. (1997). Disciplines of the Holy Spirit: How to connect to the Spirit’s power and presence. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan.

Thompson, C. (1984). Times Literary Supplement. 19 January 1984.

Welch, J. (1982). Spiritual pilgrims: Carl Jung and Teresa of Avila.New York: Paulist.

Willard, D. (2000). “Spiritual formation in Christ: A perspective on what it is and how it might be done.” Journal of Psychology and Theology, 28, 4, 254-258.

Wolters, C. (Trans). (1966). Julian of Norwich: Revelations of divine love. London: Penguin.

© Renewal Journal #19: Church (2002, 2012) renewaljournal.com

Reproduction is allowed with the copyright included in the text.

Renewal Journals – contents of all issues

Book Depository – free postage worldwide

Book Depository – Bound Volumes (5 in each) – free postage

Amazon – Renewal Journal 19: Church

Amazon – all journals and books – Look inside

All Renewal Journal Topics

1 Revival, 2 Church Growth, 3 Community, 4 Healing, 5 Signs & Wonders,

6 Worship, 7 Blessing, 8 Awakening, 9 Mission, 10 Evangelism,

11 Discipleship, 12 Harvest, 13 Ministry, 14 Anointing, 15 Wineskins,

16 Vision, 17 Unity, 18 Servant Leadership, 19 Church, 20 Life

Also: 24/7 Worship & Prayer

Contents: Renewal Journal 19: Church

The Voice of the Church in the 21st Century, by Ray Overend

Redeeming the Arts: visionaries of the future, by Sandra Godde

Counselling Christianly, by Ann Crawford

Redeeming a Positive Biblical View of Sexuality, by John Meteyard and Irene Alexander

The Mystics and Contemporary Psychology, by Irene Alexander

Problems Associated with the Institutionalization of Ministry, by Warren Holyoak

Book Reviews:

Jesus, Author & Finisher by Brian Mulheran

South Pacific Revivals by Geoff Waugh

Renewal Journal 19: Church – PDF

Revival Blogs Links:

See also Revivals Index

See also Revival Blogs

See also Blogs Index 1: Revivals

GENERAL BLOGS INDEX

BLOGS INDEX 1: REVIVALS (BRIEFER THAN REVIVALS INDEX)

BLOGS INDEX 2: MISSION (INTERNATIONAL STORIES)

BLOGS INDEX 3: MIRACLES (SUPERNATURAL EVENTS)

BLOGS INDEX 4: DEVOTIONAL (INCLUDING TESTIMONIES)

BLOGS INDEX 5: CHURCH (CHRISTIANITY IN ACTION)

BLOGS INDEX 6: CHAPTERS (BLOGS FROM BOOKS)

BLOGS INDEX 7: IMAGES (PHOTOS AND ALBUMS)

BACK TO MAIN PAGE

Click here to be notified of new Blogs

FREE SUBSCRIPTION: for new Blogs & free offers

Share good news – Share this page freely

Copy and share this link on your media, eg Facebook, Instagram, Emails:

The Mystics and Contemporary Psychology, by Irene Alexander:

https://renewaljournal.com/2012/05/20/the-mystics-and-contemporary-psychology-by-irene-alexander/

An article in Renewal Journal 19: Church:

Renewal Journal 19: Church – PDF

Also in Renewal Journals Vol 4: Issues 16-20

Renewal Journal Vol 4 (16-20) – PDF

One Reply to “The Mystics and Contemporary Psychology, by Irene Alexander”